The World’s First (and Only) Truly Phonemic Alphabet

PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY PRIMER

We start here with just a few definitions of phonetic and phonological terms.

We must first define the terms vowel and non-vowel, in a manner a bit more technical than the reader may have learned in primary school. Now a vowel is any sound (phone) in which the breath is not impeded at all. Thus, in addition to the well known a, e, i, o, u etc. taught to English speakers in primary school, this definition includes certain r– and l–like sounds in which the breath is completely unimpeded, such as the r–sound in the American pronunciation of English burr or spur.

Although this may not be relevant to our overall presentation of NAVLIPI, it is also useful to note that the vowels a (as in English but, Hindi अ), i (as in English hit, Hindi इ), and u (as in English put, Hindi उ), are denoted by many phoneticians (along with the r– and l–vowels (Hindi ऋ and ऌ) described elsewhere in this document) as fundamental vowels; all other vowels are then called derivative vowels.

In contradistinction, a non-vowel is any sound in which the breath is impeded while uttering the sound, whether partially or completely. This definition is thus a bit more technical and precise than the word consonant that many readers may have learned in primary school.

Among non-vowels, we have several possibilities:

(1) In some cases the breath can be completely stopped before the sound is uttered, as in the sounds k and p; phoneticists call these sounds plosives or stops, because the breath explodes, or is stopped before their utterance.

(2) In other cases, the breath can be partially stopped, as in the sound h, or the sound of the sh in English shoot, or the sound of the ch of German doch, or the British or American pronunciation of the th in English think. Such “hissing” or “frictional” sounds are called fricatives (in older Western literature, also called spirants). A subset of fricatives are the s–like sounds, s and sh as in English sit or shoot, which are called sibilants. Fricatives and plosives (stops) are both subsets of non-vowels. And sibilants are a subset of fricatives.

(3) In yet other cases, there is a very short-duration stopping of the breath, rather than a complete stopping followed by an explosion of the breath, as in plosives or stops. These sounds are called, self-evidently, taps or flaps, because the articulating organ lightly taps or flaps against the articulation position. These sounds are especially common in languages of the Indian subcontinent.

(4) We also have the case of sounds derived from fundamental vowels by adding an a, i or u vowel. For examples, the sounds w is essentially u + a (try saying the u and a sounds rapidly together, and you’ll get a wa). Similarly, the sound y is essentially i + a (try saying the i and a sounds rapidly together, and you’ll get a ya). These phones, e.g. w, y, r and l, are called semivowels in the older phonological literature, and approximants as more recently decreed by the IPA.

An important qualifier of sounds (phones) concerns the point of articulation in the vocal apparatus. For example, in the articulation of the sounds (phones) p or b, the point of articulation quite obviously is the two lips; so these sounds are called bilabial.

Similarly, in the articulation of the sounds k or g, the back of the tongue makes contact with a point in the upper part of the mouth called the velum, so these sounds are called velar (or, in older literature, guttural).

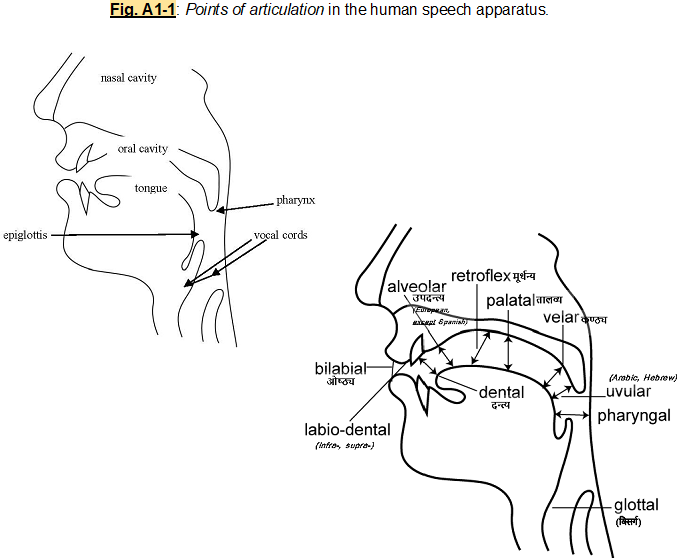

We can easily define the series of points of articulation from the back to the front of the oral cavity, as shown in the Fig. A1-1, and as described here: uvular (touching the uvulum, even further back from the velum), velar (कण्ठ्य), palatal (touching the palate, तालव्य), retroflex (tongue curled back, मूर्धन्य), alveolar (touching the alveolar ridge, उपदन्त्य), dental (touching the upper teeth, दन्त्य) and bilabial (ओष्ठ्य). Table A1-1 further qualifies points of articulation.

In addition to the above points of articulation, we also have two other designations: lateral to denote l–sounds, because, during their articulation, the tongue loses contact with the vocal apparatus on its side; and central to denote r–sounds, because, during their articulation, the tongue loses contact with the vocal apparatus on its central part.

The sharp reader may note that these articulation points are sort of arbitrary, since we can of course have continuous positions in between them! And there are positions, e.g. labiodental, wherein we have sub-positions, e.g. distinguishing whether the lower or upper lip makes contact, so infralabiodental and supralabiodental. All that is true, but in the linguistic context, the above-identified articulation points are the ones relevant to most of the world’s major languages.

We now summarize some other phonetic terminology, some of which has already been introduced above:

- Phone (भण): Any sound.

- Aspiration: Extra breath (महाप्राण), e.g. kh vs. k or ph vs. p.

- Voicing: Unvoiced (कर्कश) vs. Voiced (मृदु): “Voiced” means the vocal chords vibrate, “unvoiced” means they do not. The reader can put two fingers on their Adam’s Apple and utter the sounds p and k (unvoiced) and then b and g (voiced), and will see the difference! The sounds g, d, b are voiced (मृदु), k, t, p are unvoiced (कर्कश).

- Nasalization (अनुनासिक): The breath is partially exhaled from the nose. Quite obviously, the phones (sounds) n and m are nasals. All nasals are voiced.

- Tone (स्वर): As the reader may well know, many world languages have a determinative tone, whereby the musical tone in which a syllable is uttered can change the meaning of a word. Thus, e.g., Mandarin, the most widely spoken Chinese language, has four tones, whilst Cantonese has six.

- Click: Some languages, e.g. many of South African origin, distinguish sounds with “clicks”. English does use clicks, but they are gestural or emotive in nature, rather than part of the language proper. Thus, we have the “tsk tsk” sound, which in strict phonological terms is denoted as an ingressive (because the breath is sucked in while uttering it), dental (because the tongue touches the upper teeth) click. Similarly, the “giddyap” sound that those tending cows or horses make to these animals is denoted as an ingressive, lateral (“l-like”) click.

- Diphthong: Combination of two vowels, e.g. as in aau (as in English loud) aae (as in English Hi) Quite obviously, triphthong means a combination of three vowels, etc.

We can now cite some illustrative examples (in current Latin alphabet transcription) of the use of the phonetic terminology we have learned:

- The phone (sound) k is a velar (कण्ठ्य), unvoiced (कर्कश) plosive (or stop, स्फोट).

- The phone g is a velar (कण्ठ्य), voiced (मृदु) plosive (स्फोट).

- The phone f is a labiodental, unvoiced (कर्कश) fricative (ऊष्मन).

- The phone n is a dental (दन्त्य), nasal (अनुनासिक): plosive (स्फोट).

- The phone y (as in English yes) is a palatal (तालव्य) semivowel (अंतस्थ).

- The phone r (as in American English ramp) is a central semivowel (अंतस्थ).

- The phone l (as in American English lift) is a lateral semivowel (अंतस्थ).

In summary, all phones (sounds) can then be classified roughly according to the descriptions above, as follows; these are the only properties of phones that one needs to use to fully describe all phones:

- Point of articulation (cf. Fig. A1-1, Table A1-1, above). (From the back to the front of the speech apparatus, glottal, pharyngeal, uvular, velar, palatal, retroflex, alveolar, dental, (infra/supra)-labiodental, bilabial.)

- Degree of closure of articulating organs:

- Plosive (stop).

- Tap (flap).

- Fricative.

- Voicing:

- Unvoiced.

- Voiced.

- Nasal.

- Aspiration:

- Unaspirated.

- Aspirated.

- Tone (tonal accent) or stress accent:

- Non-tonal languages (only stress accents):

- Even in languages which are not considered tonal, stress-accent can be used to distinguish meanings of words:

- For example, in the English word content, if the accent is on the 2nd syllable, it has the meaning “satisfied”, as in “I am content”. And it will be noticed that placing the accent on the 2nd syllable also causes it to have a higher pitch (i.e. musical tone, here called acute). However, if the accent is on the 1st syllable, then the word has the meaning “composition”, as in the “Table of Contents” in a book. Again, placing the accent on the 1st syllable also causes it to be sounded in a higher musical pitch.

- Similarly, in the Russian word замо́к (zaamok), if the accent is placed on the 1st syllable, it has the meaning “lock”, and if placed on the 2nd syllable, it has the meaning “castle”.

- Even in languages which are not considered tonal, stress-accent can be used to distinguish meanings of words:

- Tonal languages (“musical” accents); e.g. Mandarin, Cantonese, Fujienese, Yoruba and Igbo:

- Varying number and nature (e.g. rising, rising-falling, level (high, mid, low etc.)) of tones.

- Although NAVLIPI is able to address all types of tones, for simplicity in this PRIMER, only Mandarin tones are listed. For detail on how NAVLIPI addresses tones of other languages, see the NAVLIPI books (https://www.amazon.com/Navlipi-Accommodating-Idiosyncrasies-Languages-Classification-ebook/dp/B00CR70RES ).

- Click:

- Non-click language (most languages of the world).

- Click language (e.g. the South African languages Nama’ and Xo!):

- Varying number and nature (e.g. whether egressive or ingressive) of clicks.