The World’s First (and Only) Truly Phonemic Alphabet

THE IPA ALPHABET IN RELATION TO UNIVERSAL SCRIPTS (ALPHABETS)

As noted elsewhere on this website, NAVLIPI conveys a combination of phonetic and phonemic information to the reader. For comparison, the alphabet of the International Phonetic Association (IPA, see https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/) is a purely phonetic alphabet and conveys NO phonemic information. Furthermore, even for a purely phonetic alphabet, the IPA alphabet (hereinafter, just “IPA”) also has certain other deficiencies (“IPA Defects”), well-recognized in the non-Western world.

For starters, it is extremely Eurocentric. It is very ad-hoc: It started with the Latin alphabet, and the mostly Western European members of the IPA in the 19th and early 20th centuries simply kept adding more letters, to describe more phones from different languages, as they needed them. So most of its backward and twisted and upside-down etc. Latin letters are difficult to recognize and non-intuitive for the lay person; and some look like they’re straight from outer-space!

The IPA also has a few errors. E.g. it does not recognize r-vowels but calls them “rhoticity”! And it still refuses to classify palatal stops (plosives) found in many languages as true stops, but rather insists on calling them affricates, an extremely Western European prejudice stemming from unfamiliarity with, and, sometimes, inability to articulate, such stops! The IPA alphabet is also counter-intuitive in many respects. In contrast, NAVLIPI attempts to be as intuitive as possible.

Some other issues relating to the IPA alphabet vs. a universal script or alphabet are:

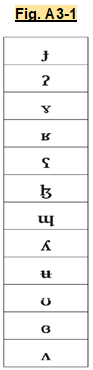

1) Unrecognizability: Many letters (glyphs, symbols) are difficult for the layman, even one who has grown up with the Latin (Roman) or Greek scripts (alphabets), to recognize. Some glyphs appear to be straight from outer space! Examples of some unrecognizable IPA glyphs are given in the Fig. A3-1 at right.

the Latin (Roman) or Greek scripts (alphabets), to recognize. Some glyphs appear to be straight from outer space! Examples of some unrecognizable IPA glyphs are given in the Fig. A3-1 at right.

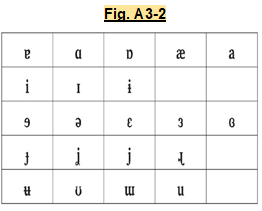

2) Confusing nature of many of the letters, a property related to the unrecognizability. Many very similar glyphs are difficult to differentiate, and are highly confusing, even to the expert. Examples among these are the various inverted and rotated e’s and a’s, the inverted/rotated/hooked, etc. variants of r and R used to represent the various alveolar trills and flaps or uvular “r’s”, and the variants of n with inward/outward hooks, etc. used for the various nasals. They are also, incidentally, very difficult to transcribe cursively and to keyboard. Examples of IPA glyphs that are confusing, even for the layperson for whom the Latin script is native are given in Fig. A3-2 above.

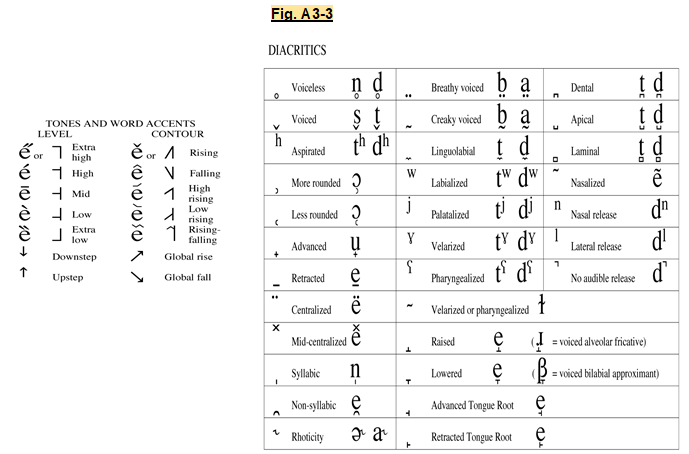

3) Too many diacritics, leading to difficult manual transcription, even when not written in cursive. Manual transcription implies pen/pencil on paper. Difficulty also implies slowness. The diacritics, etc. are further compounded by too many differentiating symbols, exponents, etc. These features of the IPA are seen in the summary of IPA diacritics presented in Fig. A3-3 below. In particular, the diacritics and accents used for tones, as shown below, are especially confusing.

4) Poor keyboarding, made even more difficult by the large number of diacritics, exponents, etc. used, and the sheer number of independent glyphs (letters). Anyone having tried transcribing a passage in the IPA using all manner of software (including embedded fonts in word processors) will readily attest to this!

5) Lack of systematic organization, lack of pedagogical sense and inapplicability for everyday use: The IPA, in its various presentations (e.g. in the IPA summary chart at the beginning of its Handbook), actually ends up using, for its “consonants”, the ancient Indian system of classification: Grouping the “consonants” based on points of articulation, starting from the back (pharyngeal/-uvular/-velar) to the front (bilabial) of the oral apparatus, and then further differentiated as plosive, nasal, fricative, etc.. However, the alphabetic order retained is still that of the Latin (Roman) alphabet. As a result, it is not clear from the IPA Summary Table (“IPA Chart”) what is the exact order of the letters, and how the alphabet would be learned, e.g., by schoolchildren. Does it, for example, start with [p], the very first letter at the top left of the IPA chart, and end with [inverted-a] [ɒ], the last vowel shown in the chart? The assumption of course is that it is not meant for schoolchildren, only for highly educated phoneticists and linguists!

6) Incompleteness: the IPA treatment of vowels does not even consider horizontal jaw position. And only two lip positions (rounded and not rounded) are considered, these being shoehorned into the IPA vowel charts. Thus, the transcription of the Tamil sound and letter ழ is difficult in the IPA. In current transcription in the Latin alphabet, this is usually transcribed as zh; e.g. as in the word புகழ், pugazh, “fame”, or as in the word Tamil itself, which is more correctly transcribed in the Latin alphabet as Taamizh. As any Tamil speaker will tell you, this sound is articulated very much like the retroflex lateral (l-sound), which also exists as a separate letter and sound in Tamil (ள), except that the jaw is forward in its articulation, which gives it its unique sound and phonemic distinction.

7) Ad-hoc, “build-as-you-go” and Eurocentric nature: These properties are transparent in the IPA, in its very nature, and  in its origins in the ad-hoc Latin (Roman) script. They are also evident in the way it has attempted to adapt to new languages with modifications of the same Latin letters. This has ultimately made the alphabet even more confusing and unwieldy. For example, some of the 2005 additions for African languages included new glyphs, as shown in the Fig. A3-4 at right below. This ad-hoc, build-as-you-go characteristic is due to the origins of the IPA in 19th-century Europe. An alphabet that started with a small modification of the Latin (Roman) alphabet to accommodate English, French and German, and then tried to gradually accommodate all the world’s languages, cannot equal, in its qualities, an alphabet or script designed ab initio, from first principles at the outset, with a knowledge of the world’s languages. And it is also unfair to the vast majority of the world’s languages and peoples, who are of non-European origin.

in its origins in the ad-hoc Latin (Roman) script. They are also evident in the way it has attempted to adapt to new languages with modifications of the same Latin letters. This has ultimately made the alphabet even more confusing and unwieldy. For example, some of the 2005 additions for African languages included new glyphs, as shown in the Fig. A3-4 at right below. This ad-hoc, build-as-you-go characteristic is due to the origins of the IPA in 19th-century Europe. An alphabet that started with a small modification of the Latin (Roman) alphabet to accommodate English, French and German, and then tried to gradually accommodate all the world’s languages, cannot equal, in its qualities, an alphabet or script designed ab initio, from first principles at the outset, with a knowledge of the world’s languages. And it is also unfair to the vast majority of the world’s languages and peoples, who are of non-European origin.

8) Sheer number of letters (glyphs), more than 172 and counting: The IPA’s individually distinct glyphs number more than 172. One reason for this is the absence of use of such glyph-saving devices as post-ops or other indicators of phonological class, as used by NAVLIPI.

9) Emphasis on “narrow transcription” rather than practical phonemics for everyday use. The IPA, in its “narrow transcription” version, is excellent for distinguishing the different pronunciation of individual speakers of the same dialect of the same language. This is no doubt a very useful property to have. However, it is of little use for practical, everyday phonemics and phonemic transcription.

10) Incorrect or nebulous classifications: As just some examples of these:

- The IPA designates the phones [s] and [z] as alveolar fricatives, which is incorrect. The alveolar articulation position is made with the tip of the tongue touching the region of the alveolar ridge, whereas the [s] and [z] phones of virtually all major languages are articulated with the apico/medio portion, i.e. a bit back from the tip, of the tongue touching either the alveolar ridge, or further up, closer to the dental area. The alveolar fricatives per se are quite different sounds from the [s] and [z]. The reader can verify this himself/herself, by first articulating the alveolar stop [t], as in the English t of sty, and then retaining that same articulation position and articulating a fricative. What ensues is something quite different from an [s]. The [s] and [z] are in fact apico/medio-dental fricatives, which is how NAVLIPI classifies them. That is to say, the contact is made with the apico/medio portion of the tongue, and the tip of the tongue itself is closer to the upper teeth than the alveolar ridge.

- The IPA does not treat of vocalic-[r] and vocalic-[l] at all, even though these phones are well established in languages from Sanskrit to Serbo-Croat. These phones were treated of by prominent modern phoneticists such as Lepsius, not to mention the ancient Indian phoneticists. Instead of recognizing these phones to accommodate vocalic-[r], the IPA comes up with a unique term, rhoticity, which is somewhat nebulously defined as an “[r]-flavor to a vowel”!

- The IPA then further confuses non-vocalic and vocalic phones by not recognizing a bilabial semivowel [w], but, rather, only a labiodental “approximant” (“approximant”, roughly, is the IPA term for a semivowel). Since this yields problems with the distinction of lateral and central vowels and semivowels, it then distinguishes some of the lateral vowels as “lateral approximants”!

- In the treatment of both Hindi and Sindhi in its main and most popular publication, the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, the palatal stops, of which there are four in nearly all North Indian languages (unvoiced/voiced, unaspirated/aspirated combinations), are treated as affricates. The reasons for this are not hard to find, and lie, unfortunately, in the still Eurocentric view of the IPA: Since Western European languages do not phonemically differentiate between aspirated and unaspirated stops, Western Europeans always pronounced these Indian palatal stops with aspiration and also affricatization, as a result of which they always came out as affricates, exactly like the identical affricates in their own languages. However, Indians articulate these clearly as stops, not affricates, and the highly adept ancient Indian phoneticists recognized them as stops (sparsha, स्पर्ष), not a combination of stops and fricatives (uushman उष्मन). Strangely, though, the IPA does recognize palatal stops elsewhere, e.g. in its treatment of Irish in the very same IPA Handbook! Thus, in a sense it contradicts itself, while also, unfortunately, displaying some pro-European prejudice! Now anyone who has heard an Irishman’s and an Indian’s pronunciation of the palatal unvoiced stop (IPA designation [c]) will acknowledge that they are identical! One may thus speculate that the early classification of the Indian palatal stops as affricates, and not true stops, emanated from audio (spectrographic) analysis of the Indian sounds uttered into a microphone by a non-Irish European sometime in the 19th or 20th centuries!

- Another example of erroneous classification is the (incomplete) IPA treatment of vowels. For, as noted above, the IPA does not even consider the horizontal jaw position, and considers only two lip positions (rounded and not rounded), these being shoehorned in to the IPA vowel charts. In contrast, even Pike recognized many different lip and jaw positions, and NAVLIPI treats of two horizontal jaw positions and three lip positions. NAVLIPI does not consider any more lip and jaw positions for reasons of discretization and practicality.

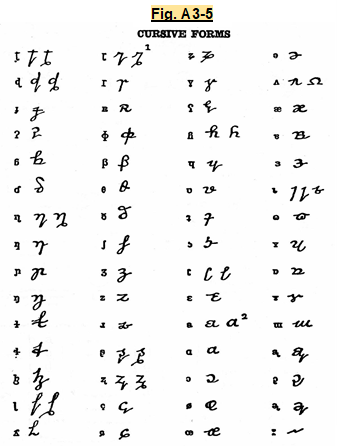

11) Poor amenability to cursive writing, as Fig. A3-5, at right, shows.

12) Finally, the most important deficiency of all: inability to account for the phonemic idiosyncrasies of the world’s languages:

This is perhaps the IPA’s most important deficiency, although, admittedly, it is also a deficiency of all scripts prior to Navlipi. This deficiency is reflected in the following examples:

- The IPA is unable to indicate to the native English speaker reading Hindi in the IPA that the unaspirated [p] and aspirated [ph] have distinct phonemic values in Hindi, whereas they have the same values in English.

- Similarly, an English speaker reading Mandarin would not be able to tell that [p] and [b] have the same value in Mandarin, or that [r] and [l] have the same value in Japanese.

- Conversely, the Arabic speaker reading English in the IPA for the very first time could not guess that the [b], the only bilabial that he/she is familiar with, has an unvoiced counterpart, [p], that has a different value than the [b].

- As another example, the IPA is unable to convey, through its orthography alone, that in Hindi, the phones [w] (bilabial semivowel) and [v] (labiodental voiced fricative) constitute part of the same phoneme and are freely interchanged.

- In a similar vein, the IPA cannot convey that, in Parisian French and “proper” German (Hochdeutsch), the phones [x] (velar unvoiced fricative), [r] [alveolar flap] and [rr] (alveolar trill) constitute part of the same phoneme and are frequently interchanged.